Student stories: Completing a ledger conservation project

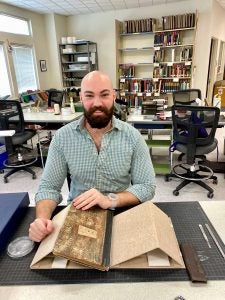

Conservation lab graduate assistant Winston Sandahl completed conservation repairs on one of ECU’s Rev. Frederick C. Douglass ledgers. Winston’s thorough repairs included cleaning, mending tears, rebinding the ledger and making it ready for digitization. This ledger was in a fragile state before conservation efforts, but is now in stable condition suitable for researchers to learn about some of the African American community’s familial networks, military service history and challenges in obtaining federal rights and benefits following the American Civil War and the collapse of Reconstruction.

The following is a summary from Sandahl:

We see all kinds of books, bindings and contents when items arrive in conservation. Many items receive a quick fix or a solidly constructed box to protect them before heading back up to Special Collections, but our curatorial staff had flagged a particular legal ledger for needing some extra attention.

In this instance, the ledger belonged to Frederick C. Douglass, a black lawyer, minister and teacher from New Bern. Douglass had assisted in processing the pension claims for black veterans and widows of veterans who had served in the American Civil War. Born Fredrick Huggins in 1850 to an  enslaved Mary Norman, Douglass witnessed first-hand the family ties that he would later defend after the war. He renamed himself deliberately in correspondence with the abolitionist Frederick Douglass, possibly to solidify a bond to the hardships of maintaining freedom and equality for African Americans. By 1885, Douglass had built up a reputation for knowing his clients personally and having an intimate acquaintance with the local community and pension bureau. The testimony that Douglass

enslaved Mary Norman, Douglass witnessed first-hand the family ties that he would later defend after the war. He renamed himself deliberately in correspondence with the abolitionist Frederick Douglass, possibly to solidify a bond to the hardships of maintaining freedom and equality for African Americans. By 1885, Douglass had built up a reputation for knowing his clients personally and having an intimate acquaintance with the local community and pension bureau. The testimony that Douglass

collected in his ledgers provides researchers information about dynamics, life and the history of families in post-Reconstruction eastern North Carolina.

The successful work of Frederick C. Douglass resonates a sentiment of progress despite major struggles for the African American community following the Civil War. This ledger represents multiple facets: an artifact of the late 19th century, an example of a preserved legal ledger and a collection of primary information connecting researchers to the work that Douglass conducted during a paramount turning point in American history.

It was important to preserve this history and it became clear that an intensive level of treatment was warranted.

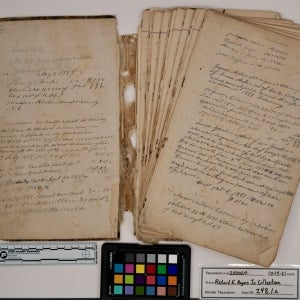

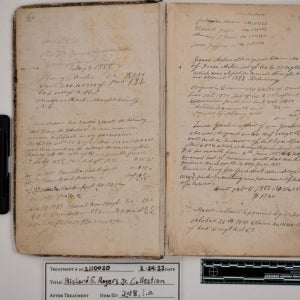

This historic ledger, dating to the 1880s and 1890s, demonstrates primary accounts of Douglass’ work. Although sturdy, the paper that this ledger was written on feels fragile to the touch. Like many business account books of the period, the book had a wire binding—iron staples held the pages to a glued cloth lining at the spine, instead of the more traditional sewn thread. While it presented a new, modern method of mechanized bookbinding, the iron wires of the binding do not hold up to time (and humid North Carolina summers). As is the case for many of these ledgers, the wires had rusted away, leaving the pages loose and damaged. Fragments of paper had become detached, and any handling would further damage it. To enable people to safely access and read these accounts, conservation treatment would be needed.

On examination in the lab, the condition was documented, to keep a record of how the book was originally bound. The remaining staple fragments were removed and each folio — pages folded in half to form two pages which are then stacked together to form a signature — was reinforced with thin tissue so that the signatures could withstand being resewn together. Repairs included mending tears of various sizes and removing dirt and soot that has collected over 125 years. In areas of heightened concern, for example the edges of pages that had become misaligned over time, pieces of thin tissue were adhered to reinforce them. The boards of the ledger are covered with a handmade marbled paper that has maintained its vibrant colors despite over a century of changing storage environments. However, there were some areas where the original material was missing or lost.

Originally, the book was bound with a black leather spine that was no longer present with the ledger by the time it was acquired by our Main Campus Library. This area, as well as the edges of the covers, needed to be mended and visually re-integrated, to draw attention away from areas where the repairs had taken place. A new spine was pigmented black and textured to match the remaining fragments of leather on the covers. Special kozo tissues along the edges of the board were custom pigmented to match the decorative paper of the cover. The entire ledger was rebound in a manner that will both allow researchers to handle it safely, as well as preserve an appearance appropriate to the appearance of the original binding.