The B-1 Navy Band: A Symphony of Courage and Change

Remembrance and Records: World War II Through Archival Collections

Over the next year, in commemoration of the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II, Joyner Library Special Collections will be highlighting items from the East Carolina Manuscripts Collection that relate to the conflict and the individuals who served.

During World War II, the U.S. Navy B-1 Band made history as the first African Americans to serve in the modern Navy at ranks higher than a messman. Comprising primarily students and graduates from North Carolina A&T College, this ensemble not only showcased exceptional musical talent but also played a pivotal role in challenging racial segregation within the U.S. military.

Formation and Early Challenges

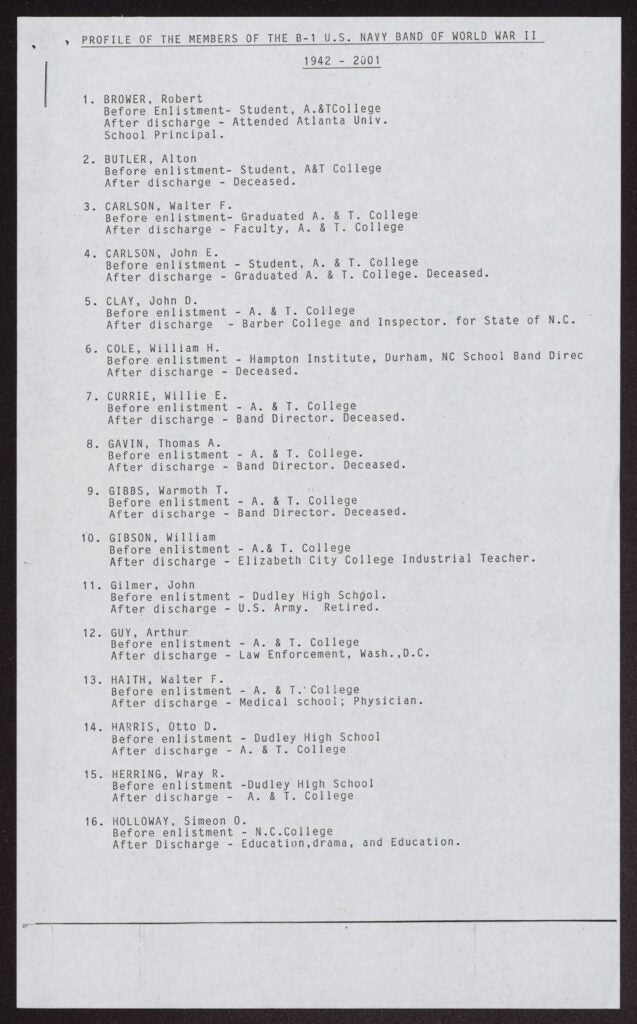

Profile of the members of the B-1 U.S. Navy Band of World War II, 1942-2001. Item from the Calvin F. Morrow Collection (#908), East Carolina Manuscript Collection, J. Y. Joyner Library, East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina, USA.

In 1942, the Navy sought to expand roles for African Americans beyond custodial positions. Recognizing an opportunity, a group of talented musicians from North Carolina A&T College, along with nine students from Dudley High School, enlisted to form what would become the B-1 Band. James B. Parsons, the band director at Dudley High School, was appointed as the band’s leader after A&T’s director, Bernard Mason, was unable to pass the required physical examination.

Despite their qualifications, the band members faced systemic racism, including exclusion from the Navy’s School of Music, which did not admit Black students at the time. Instead, they relied on their training and cohesion to prepare for service. After enlisting, they were sent to Norfolk, Virginia, for basic training. Instead of focusing on music, their early days consisted of physical conditioning, drills, and vaccinations. One band member recalled that they “did everything but get up and exercise in the morning” when it came to musical preparation.

The band members also encountered racism at every turn. Despite being enlisted as musicians, they were not treated as equals to their white counterparts. They were often housed separately, subjected to menial tasks, and denied access to the Navy School of Music. Instead, they had to train among themselves, forging their path in an institution that had not yet recognized their full potential.

Service in Chapel Hill: The Pre-Flight School Band

From August 1942 to May 1944, the B-1 Band was stationed at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where they served as the official band for the Navy’s Pre-Flight School. Their presence at a white university in the Jim Crow South was groundbreaking. While they were not allowed to live on campus, they were given a separate building and provided music for official events, including daily marches and ceremonies.

Despite their recognized musical talent, the band members continued to encounter segregation and exclusion. A master’s thesis about the Pre-Flight School at UNC-Chapel Hill mentioned a “colored band from A&T” but incorrectly stated that no members could be located for interviews. This is despite many oral histories with members of the B-1 Navy Band available to researchers in the East Carolina Manuscript Collection. This is just one example of how the band members and their contributions have been erased from the official historical records, whether intentionally or by accident.

B-1 Navy Band group photograph from the United States Navy Pre-Flight School Band yearbook, 1944. Item from the Wray Raphael Herring Collection (#810), East Carolina Manuscript Collection, J. Y. Joyner Library, East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina, USA.

Deployment to Pearl Harbor

In May 1944, the band was transferred to Manana Barracks at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, the largest posting of African American service members during the war. There, they continued their musical duties, performing for troops and participating in parades. Despite being far from home, the band maintained high morale and professionalism, contributing to the war effort through their performances. Notably, after the original members began mustering out in October 1945, their replacements included saxophonist John Coltrane, who would later become a jazz legend.

Upon arriving in Hawaii, they quickly realized they were once again in an environment where the Navy did not know how to utilize them. They were placed in deplorable living conditions, housed between two segregated units, and denied their instruments for an extended period. Some were even assigned non-musical duties, such as painting and cutting bamboo for a theater. One member recalled that the band was “out of place” and that the Navy “didn’t know what to do with us.”

Even in these trying circumstances, the band members found ways to maintain their musical excellence. They performed for hospital ships, officers’ dances, and military ceremonies, proving their worth despite the systemic racism they faced. The band was divided into three musical groups: a full concert band, a dance orchestra, and a show band that performed skits and comedic performances.

One of the key figures in organizing entertainment was Otto Harris, a talented musician and natural comedian who played multiple instruments. He not only contributed musically but also gave many band members their nicknames, fostering camaraderie within the group.

The Fight for Recognition

One of the most striking aspects of the B-1 Navy Band’s history is the lack of recognition they received both during and after their service. Despite being the first all-Black Navy band, their contributions were largely omitted from official records.

During their time in Norfolk, Navy officials even staged a disturbing event where Black mess attendants were given instruments and instructed to pose as the B-1 Band for photographs—an act that further marginalized the actual musicians and obscured their contributions. Decades later, the band members and historians had to painstakingly gather documentation and personal accounts to prove their existence and service. As stated in the U. S. Navy B-1 Band Group Oral History Interview from the East Carolina Manuscript Collection, “The Navy had no evidence we were there. We were there, but nobody knew we were.”

Despite these challenges, the legacy of the B-1 Navy Band endures. Their service paved the way for future generations of Black musicians in the military. They were pioneers in a segregated institution, and their persistence helped break down racial barriers within the armed forces.

Post-War Legacy and Impact

After World War II, many members of the B-1 Band returned to North Carolina and pursued higher education at North Carolina A&T College. A considerable number became educators, influencing future generations through their dedication to music and teaching. Some members formed the “Rhythm Vets,” a regional band that gained popularity in Greensboro and performed the soundtrack for the 1947 black-cast musical comedy featurette Pitch a Boogie Woogie. This film, shot in Greenville, North Carolina, has been preserved and is included in the 1988 documentary Boogie in Black and White.

The contributions of the B-1 Band were formally recognized on May 27, 2017, with the installation of a historic marker in Chapel Hill. This date marked the 75th anniversary of their enlistment and honored their role in integrating the U.S. Navy and their impact on civil rights.

The story of the B-1 Navy Band exemplifies courage, resilience, and the pursuit of equality. Their legacy continues to inspire and serve as a testament to the profound impact that dedicated individuals can have in challenging and transforming institutionalized discrimination.

Their contributions remind us of the importance of preserving and telling the stories of those who paved the way for progress. Thanks to the efforts of historians and the band members themselves, their legacy is now being properly acknowledged, ensuring that their place in history is never forgotten.

The B-1 Navy Band may have been overlooked for decades, but their story is now rightfully being recognized as a crucial chapter in the history of the U.S. Navy and the fight for racial equality.

Visit the Ship’s Log, as well as Joyner Library’s social media channels, to learn more about materials related to World War II that are a part of the East Carolina Manuscripts Collection’s holdings. Joyner Library Special Collections will be displaying an exhibit of items and individual stories related to World War II during the summer and fall of 2025.

Sources:

- Abe Thurman Oral History Interview (#OH0216), East Carolina Manuscript Collection, J. Y. Joyner Library, East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina, USA.

- Calvin F. Morrow Collection (#908), East Carolina Manuscript Collection, J. Y. Joyner Library, East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina, USA.

- John Gilmer Oral History Interview (#OH0214), East Carolina Manuscript Collection, J. Y. Joyner Library, East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina, USA.

- R.A. Fountain. “U.S. Navy B-1 Band – R.A. Fountain,” July 28, 2022. https://rafountain.com/navy/overview/.

- Roy Lake Oral History Interview (#OH0231), East Carolina Manuscript Collection, J. Y. Joyner Library, East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina, USA.

- Simeon O. Holloway Oral History Interview (#OH0215), East Carolina Manuscript Collection, J. Y. Joyner Library, East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina, USA.

- U. S. Navy B-1 Band Reunion Collection (#0971) East Carolina Manuscript Collection, J. Y. Joyner Library, East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina, USA.

- U. S. Navy B-1 Band Group Oral History Interview (#OH0213), East Carolina Manuscript Collection, J. Y. Joyner Library, East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina, USA.

- Wray Raphael Herring Collection (#810), East Carolina Manuscript Collection, J. Y. Joyner Library, East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina, USA.