The Battle of Okinawa: The Pacific War’s Bloodiest Chapter

Remembrance and Records: World War II Through Archival Collections

Warning: The following content features accounts of war and human suffering. Content may be upsetting to some.

Over the next year, in commemoration of the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II, Joyner Library Special Collections will be highlighting items from the East Carolina Manuscripts Collection that relate to the conflict and the individuals who served.

Invasion of Okinawa, A Pictorial Review. U.S. Navy Memorial Foundation Collection: Paul R. Lash Papers (#677-073), East Carolina Manuscript Collection, J. Y. Joyner Library, East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina, USA.

The Battle of Okinawa

September 2, 2024 marks 79 years since the formal surrender of the Empire of Japan in World War 2. The dropping of two atomic bombs on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, coupled with the impending threat of a third and a ground invasion of mainland Japan by U.S. forces, pushed Emperor Hirohito to sign the Instrument of Surrender on the deck of USS Missouri. This moment was the culmination of intense fighting and the loss of many lives across three and a half years.

One of the bloodiest and most crucial victories by U.S. forces to set up the surrender of Japan was the Battle of Okinawa. Beginning April 1, 1945, Okinawa was the final major obstacle in their path. Starting with heavy shelling by U.S. Naval Forces, a ground invasion of around 60,000 U.S. Marines and soldiers from the U.S. Tenth Army would follow. The battle would end in the capture of the island at the cost of approximately 49,000 American lives. The story of Okinawa, especially its planning and early days, can be found throughout the East Carolina Manuscript Collection donated by those who served.

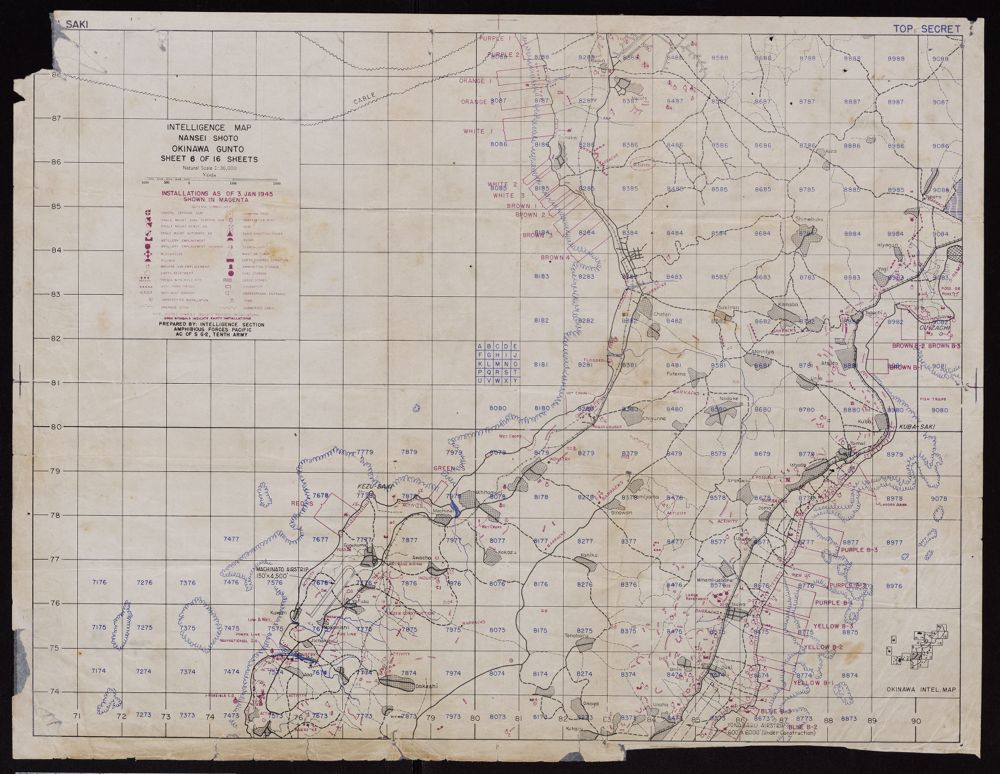

Having identified the strategic importance of Okinawa, the intelligence community began planning for an eventual assault months ahead of “L-Day” on April 1st, 1945. Nicknamed “Operation Iceberg”, the U.S. Armed Forces in the Pacific conducted reconnaissance of the island, producing maps and aerial photographs to assist with the planning. An example includes the Intelligence Map Nansei Shoto Okinawa Gunto produced in January 1945.

Maps such as these identified natural obstacles to avoid, such as flooded areas in grid 8978; targets to eliminate, like a railroad station in grid 8280; or sites of strategic importance, such as the Yonabaru Airstrip in grid 8473. Additional examples of maps used in the campaign can be found in Cdr. Lynn F. Barry and Betty J. Barry Collection

#1298 and U.S. Navy Memorial Foundation Collection: Roy A. Dye, Jr., Papers #0677-065.

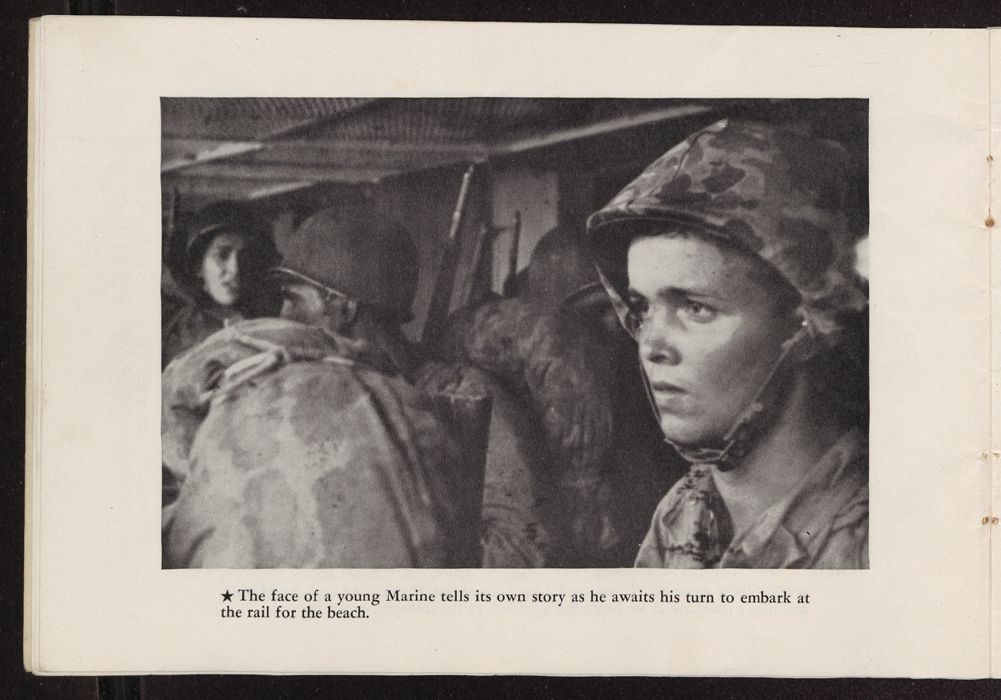

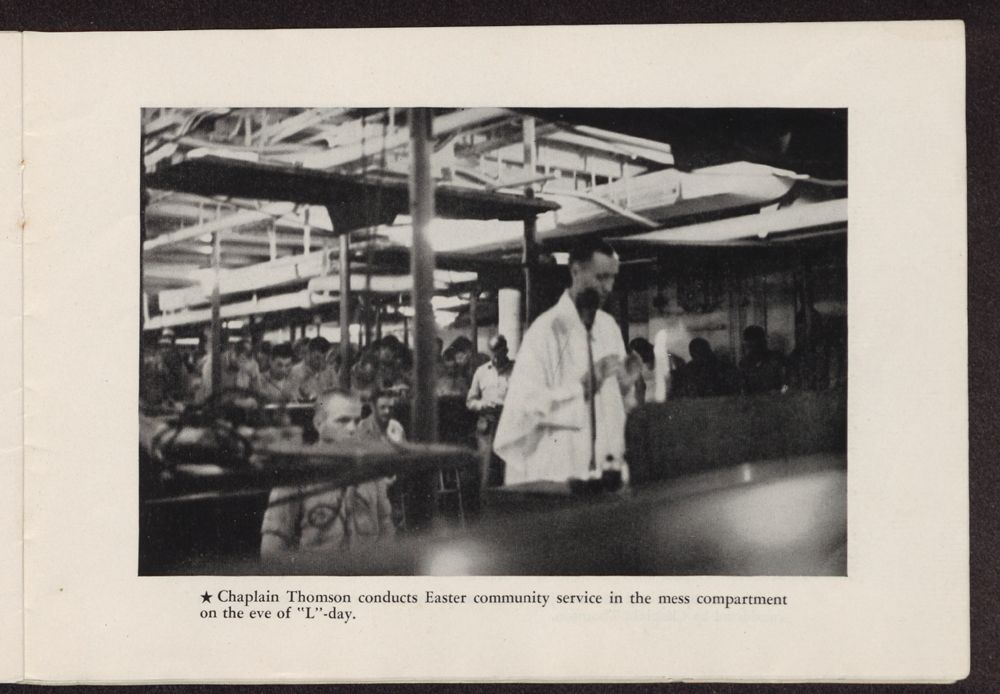

As the preparation sped up in the wake of the victory at Iwo Jima, written plans were developed and disseminated to the participants. Some examples of these include typed guides for rehearsals of the invasion, as well the plan for the first few days of the invasion titled “ Informational Outline for Operation Iceberg” included in Lieutenant Roy A. Dye, Jr.’s papers. While officers, such as Dye, were absorbed in the logistical planning, the enlisted men prepared by eating one last good meal and attending religious services.

Invasion of Okinawa, A Pictorial Review. U.S. Navy Memorial Foundation Collection: Paul R. Lash Papers (#677-073), East Carolina Manuscript Collection, J. Y. Joyner Library, East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina, USA.

As the April 1, 1945 “L-Day” drew near, U.S. Navy ships from Task Force 58 (TF58) began “softening” up the beaches for an amphibious assault on Okinawa. Captain Leon Grabowsky was a part of TF58 aboard the USS Leutze and speaks about his experience in the Leon Grabowsky Oral History Interview June 7, 1991.

Also at the forefront of the battle was Captain Willard W. DeVenter aboard the USS Arkansas who discusses his story of the battle in the Willard W. DeVenter oral history interview, August 27, 1996.

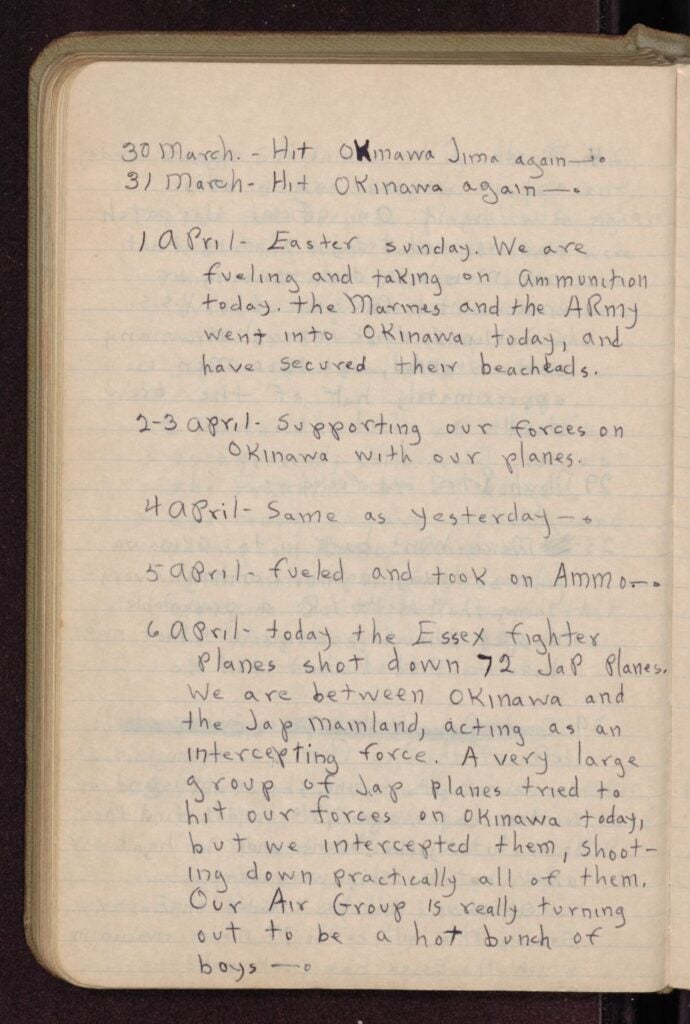

Both Grabowsky and DeVenter discuss the overwhelming amount of Japanese kamikaze attacks that plagued TF58 at the beginning of the invasion as part of the Japanese operation “Ten Go”. Grabowsky recounts facing one onslaught of over 300 kamikazes attacking T58 during the early stages of the invasion and sinking the USS Newcomb, while DeVenter details his role in preventing suicide attacks from directly striking the Arkansas. Additional stories from TF58 and the perspective of the battle from the sea can be read in the Diary of John A. Yeager aboard U.S.S. Essex whose log detailed daily events during the battle.

Diary of John A. Yeager aboard U.S.S. Essex, August 1943 to September 1945. U.S. Navy Memorial Foundation Collection: John A. Yeager Papers (#677-053), East Carolina Manuscript Collection, J. Y. Joyner Library, East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina, USA.

For the men on the ground, the fighting was no less intense. While the East Carolina Manuscript Collection does not include much from the perspective of the Marines or Army enlisted who fought on the island, DeVenter’s account includes an anecdote that captures the difficulty of fighting on the rain-soaked, cave-dotted, rocky island under heavy fire from the entrenched Japanese soldiers. In an attempt to support forward progress on the island, DeVenter was sent with a detachment of Marines to radio-in positions, offering air support for those trying to take the Shuri lines. DeVenter details the difficulty finding cover under the barrage of Japanese bullets and the danger of getting to cover even when present: “I never got there. I never made it. So many bullets, you know, you end up down on the ground and boy, you start digging.”

After 3 months of heavy fighting, U.S. troops would eventually wrest control of Okinawa from the Japanese. Having secured their staging base for the planned invasion of Japan preparation for the final phase of the Pacific War began. For their efforts, the heroism and sacrifice of the enlisted men at Okinawa were recognized. Both Grabowsky and DeVenter distinguished themselves with Grabowsky being awarded the Navy Cross for his heroism rescuing survivors of the sinking Newcomb and DeVenter being awarded a Purple Heart for injuries sustained during kamikaze attacks on the Arkansas. Additionally, entire units and ships were cited

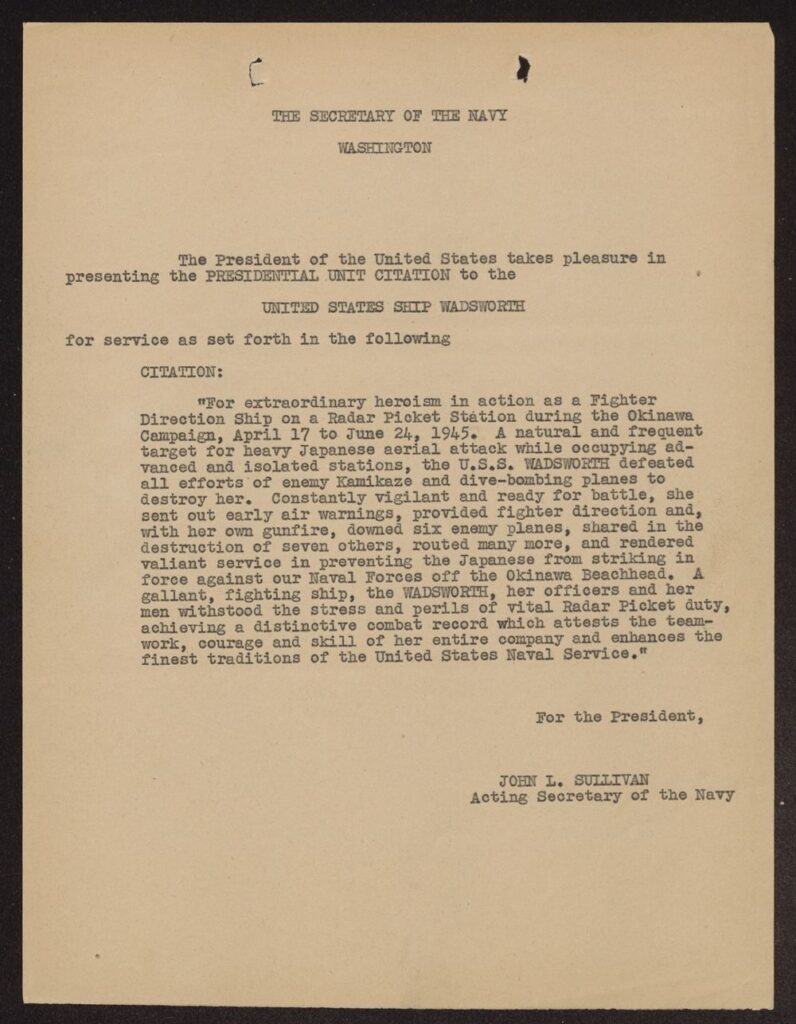

Presidential Unit Citation to the USS Wadsworth. George M. Hagerman Papers (#575), East Carolina Manuscript Collection, J. Y. Joyner Library, East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina, USA.

including the USS Wadsworth who received a Presidential Citation for the efforts of its crew and officers protecting TF58 from kamikaze attacks.

Additional stories from the Battle of Okinawa can be found by searching our Collection Guides or through our Library Catalog.

Visit the Ship’s Log, as well as Joyner Library’s social media channels, to learn more about materials related to World War II that are a part of the East Carolina Manuscripts Collection’s holdings. Joyner Library Special Collections will be displaying an exhibit of items and individual stories related to World War II during the summer and fall of 2025.

Resources:

- Battle of Okinawa, retrieved from: https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/topics/battle-of-okinawa

- Battle of Okinawa: 1 April–22 June 1945, retrieved from: https://www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/wars-conflicts-and-operations/world-war-ii/1945/battle-of-okinawa.html

- Marines in World War II Commemorative Series, retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/npswapa/extcontent/usmc/pcn-190-003135-00/sec1.htm

- Task Force 58 / 38: Okinawa, retrieved from: https://www.taskforce58.org/okinawa/