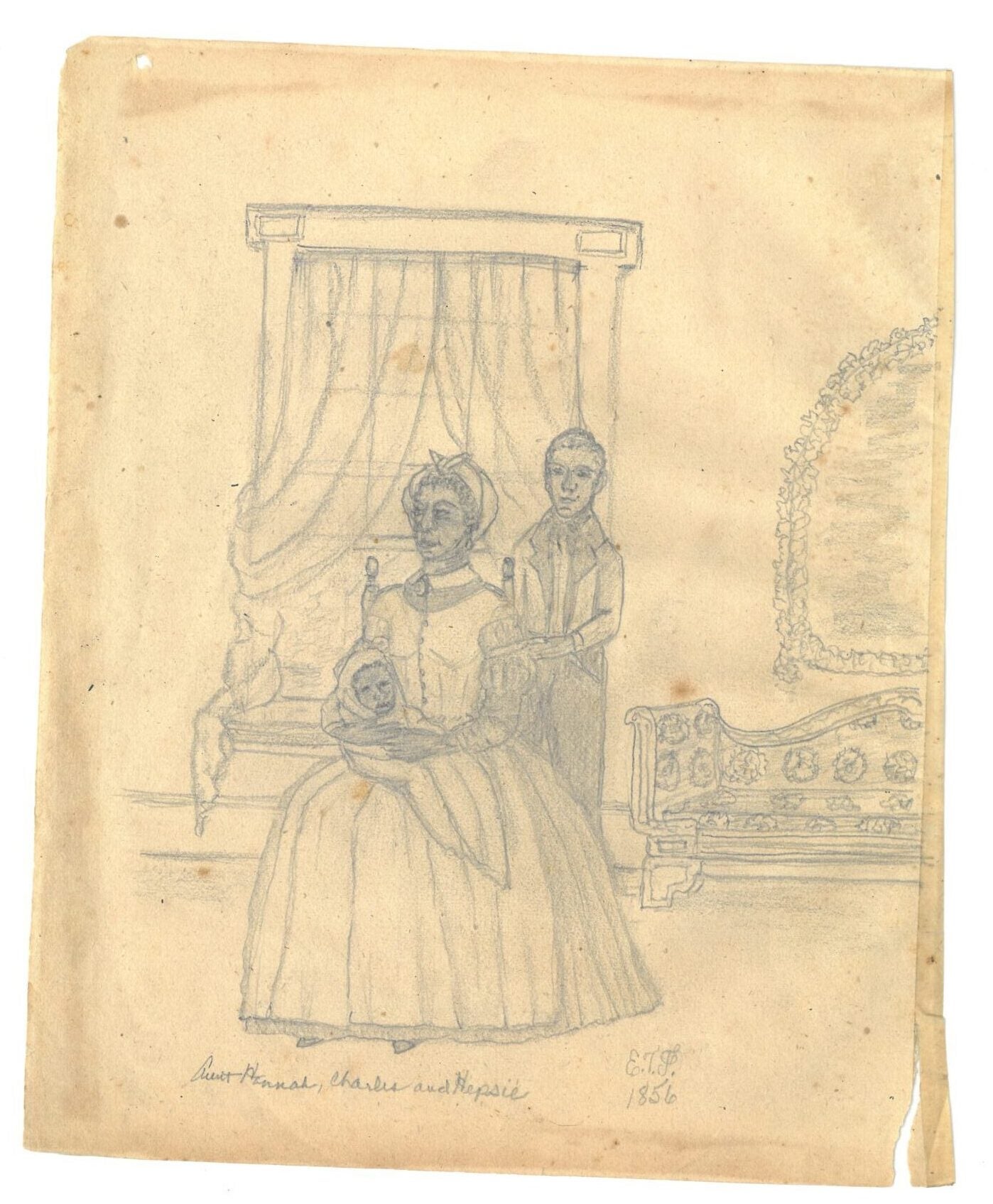

Hannah and Her Family, 1856

This sketch of an enslaved North Carolina African American family, signed ETF [Miss Elizabeth “Bettie” Taylor Flowers (1838-1916)], was a gift to Joyner Library from John Baxton Flowers, III [Mr. Flowers] in 2011. At that time, Mr. Flowers described its provenance in a letter to Martha Elmore, a curator in the Manuscripts Department, which is the source for this the information in this post. He wrote that he found it “tucked into the 1806 edition of the Book of Common Prayer belonging to John Flowers of Poplar Hill Plantation in Wayne County, N.C., which is now in my possession. It came to me from my cousin, the late Mrs. Lawrence Eugene Bradsher (Elsie Lee Kornegay) of Goldsboro, N.C. about 1976.” The drawing was accompanied by other drawings of family members and homes “tucked into” the same prayer book and preserved in the same archival container today.

Hannah and Her Family Sketch. John Baxton Flowers, III Papers (#1001), East Carolina Manuscript Collection, J. Y. Joyner Library.

Elizabeth “Bettie” Flowers, who made the sketch, was a daughter of Alfred and Margaret Kornegay Flowers (1809-1862), of Wayne County, N.C. She and her sister, Sarah Eliza, attended Everittsville Academy at Everittsville, in Wayne County. There, Bettie studied art and began to sketch. The sisters later transferred to the Clinton Female Institute in Clinton, Sampson County, N.C. where Bettie continued to study art. The sketch may or may not have any artistic merit, but it does tell a great deal about both master-slave relationships and family dynamics in antebellum North Carolina.

According to Flowers family tradition, Bettie made the sketch, dated 1856, in the parlor of the “big house” at Flowery Dale Plantation, where the Flowers family lived. The décor of the room does seem appropriate for the time. The main subject of the sketch is ‘Aunt Hannah’ who had been a Kornegay family slave. When Bettie’s mother, Margaret Kornegay, married Alfred Flowers in 1828, she recruited Hannah to become a nanny to her children. Hannah, who was of mixed race, was only eight years old when Margaret married, but a strong bond developed between Margaret and Hannah. According to Mr. Flowers, Hannah’s father was rumored to be Alfred Kornegay, the son of Captain Jacob Kornegay of Duplin County, and therefore, Margaret Flowers’ cousin.

In any case, Hannah was an intimate and influential member of the household. According to Mr. Flowers’ letter, Alfred and Margaret Flowers had a house built for her when she was expecting her first child, Charles, in 1843. Charles is the boy standing behind Hannah in the sketch. Charles, whose father was rumored to be Alfred Flowers, also became a favored member of the household and served as head houseman at the plantation. He also worked in the stud raising racehorses. Charles’ last master was Robert Bryan Flowers, the eldest son of Alfred and Margaret Flowers. Robert later gave Charles property in Wayne County where Charles and his wife, Rachel, built a home. In 1899, Robert Flowers gave his eldest son 50 acres next door to the land he had deeded to Charles Flowers. Mr. Flowers wrote that his own grandfather, John Baxton Flowers, built his own family home on the site the following year. His children grew up with those of ‘Uncle Charles’ and ‘Aunt Rachel’ who lived next door.

The other figure in the sketch is Hannah’s infant daughter, Hephzibah, born in 1856. Hephzibah became Mr. Flowers’ grandfather’s beloved nanny “Aunt Hepsie”. Mr. Flowers writes of his grandfather’s relationship with Hepsie:

“He loved and cared for her as long as she lived. He had such warm and wonderful stories of her and her place in the family circle. When the big house on the plantation caught fire early in 1878 and burned to the ground, it was ‘Aunt Hepsie’ who picked up my grandfather, then only four years old, and carried him and his sister Margaret, onto the lawn where they witnessed the house burning and all the people trying to get things from the house before they were burned. It was a memory that he and his younger sister Margaret, never forgot, nor did they ever have anything but wonderful things to say of ‘Aunt Hannah’ and her children. To my knowledge there was never any public acknowledgement of the mulatto Flowers children as blood kin, but privately, there were close and warm relations. It has never been known who the father of Hephzibah was, but she too was a mulatto, as the census records will attest. She never married.”

Mr. Flowers writes that family tradition holds that ‘Aunt Hannah’ and her children and a few other slaves working in and around the house thought themselves ‘superior’ to the other slaves on the farms, who may in turn have resented the favoritism shown the house slaves. Aunt Hannah and her descendants retained their sense of superiority even after the end of slavery. Upon being freed, they took the family name, Flowers, and remained with the family afterward for many years.

Note: Mr. Flowers entire letter is available for examination together with the sketch of Hannah, Charles and Hephzibah and the other sketches found in the Book of Common Prayer in the John Baxton Flowers, III Papers (#1001.40.ze).

(Transcript of letter from John Baxton Flowers, III to Martha Elmore)

April 25, 2011

Ms. Martha Elmore

East Carolina University Manuscript Department

Re: Drawings sent in the additional papers of John Baxton Flowers III

The drawings of Simon Flowers of Wayne County, N.C. (1721-1795) and of George Kornegay, Sr. (1704-1773) ‘The Palatine’, were found tucked into the 1806 edition of the BOOK OF COMMON PRAYER belonging to John Flowers of Poplar Hill Plantation in Wayne County, N.C., which is now in my possession. It came to me from my cousin, the late Mrs. Lawrence Eugene Bradsher (Elsie Lee Kornegay) of Goldsboro, N.C. about 1976. Both drawings were tucked into separate parts of the prayer book, and from what I can tell, they were likely drawn by the same person, traditionally said to be Anne Civil Kornegay (daughter of Capt. Jacob Kornegay of Duplin County, a son of George Kornegay, Sr.). Anne (or Anna) was married twice: the first time to William Duncan of Duplin County, N.C. and the second time to John Flowers of Wayne County. She was John’s second wife and had two children by John Flowers. The date of their marriage is given as 1806, and she died in 1839, ‘a very old woman’ as our family tradition firmly states. Family tradition also states she was the artist of the sketch of George Kornegay, Sr. as it is written on the back: “Anna C. Kornegay 1770.” The sketch of John Flowers is only labeled at the top as “Grandpa Simon Flowers 1791.” Tradition says that Anne Kornegay Duncan Flowers was his daughter-in-law, and that she inay have called him ‘Grandpa.’ She is not thought to have personally signed either sketch and I know of no known signature for Anne Kornegay Flowers.

The paper they are drawn on is old, and appears to me to have been ‘scraps’ of paper that she used to sketch on. Both sketches appear to have been posed, as the subjects are sitting in an upright position. Little beyond this is known of them. They passed down in the BOOK OF COMMON PRAYER, which also has some family dates of birth and death in it, from John Flowers of Poplar Hill (1755-1812), eldest son of Simon Flowers cited above, to his eldest son, Samuel Flowers, also of Wayne County, who was born in 1778 and died in 1861. It came into the possession of one of two granddaughters (children of his eldest son, Alfred Flowers -1806-1846), Sarah Eliza Flowers who married George Washington Bridgers, grandparents of Mrs. Bradsher, or they belonged_to Miss Elizabeth Taylor Flowers, sister to Mrs. Bridgers, who lived with the Kornegay family in Goldsboro until her death in 1916, and Mrs. Bradsher said that her aunt gave the prayer book to her. Elsie Lee Kornegay, later Mrs. Bradsher told me she wanted the prayer book to return to the Flowers family. So, either way, the book and its contents came down from Mrs. Bradsher to John Baxton Flowers III, great grandson of Robert Bryan Flowers, the eldest brother of both Sarah Flowers Bridgers and Elizabeth T. Flowers.

You might note that the John Flowers of Poplar Hill Plantation, Wayne County is the same as the John Flowers who owned the Price-Struther map of North Carolina, which I, John Baxton Flowers III, gave to the Joyner Library some years ago. That map was found in an old barn on the tract ofland called Flowery Dale Plantation (extending into Wayne, Sampson and Duplin counties), which belonged to Alfred Flowers and his heirs. At the time the map was found and given to my grandfather, J.B. Flowers of Mount Olive, N.C., the barn in which it was found belonged to his brother Mr. Robert Lee Flowers.

I also gave a map of the United States, dating to the mid-19th century, along with maps of the Holy Land, to Joyner Library, which belonged to the Alfred Flowers of Flowery Dale Plantation, cited above.

This last sketch was done by Miss Elizabeth Taylor Flowers (1838-1916). Miss Flowers was a daughter of Alfred and Margaret Kornegay Flowers (1809-1862), the daughter of Jacob and Elizabeth Wiggins Kornegay of Wayne County, N.C. This Jacob was sometimes called ‘Jacob Kornegay, Jr.’ as he was the nephew of Captain Jacob Kornegay of Duplin County, a prominent civic official and planter.

Miss Flowers and her sister, Sarah Eliza, were educated first at home by their mother, Margaret, and then sent to the fashionable Everittsville Academy at Everittsville, south of Goldsboro in Wayne County. At the Everittsville Academy Elizabeth (called Bettie) studied art, and began to sketch. She and her sister were transferred to the Clinton Female Institute in Clinton, Sampson County, N.C. where ‘Bettie’ Flowers had further art instruction, and a number of her sketches are extant in the family connection today.

This particular sketch is of ‘Aunt Hannah’ a Kornegay slave who came with Margaret Kornegay when she married Alfred Flowers in 1828, and who in time became the mammy to the younger Flowers children. Hannah, a mulatto, was only eight years old when she came to Flowery Dale Plantation with her mistress, but the bond between Margaret and Hannah was strong. Hannah’s father was rumored to be Alfred Kornegay the wild son of Captain Jacob Kornegay of Duplin County, making her a cousin to Margaret Flowers.

Hannah became the most prominent and powerful female slave on the Flowers plantation, and Alfred and Margaret Flowers had a house built for her when she was grown and was pregnant with her first child, Charles, who was born in 1843. Charles was said to be the son of Alfred Flowers. Charles Flowers grew up to be head houseman at Flowery Dale and a faithful retainer. He also worked at times in the stud that produced some of the finest racing horses in the region. His last master, Robert Bryan Flowers, the eldest son of Alfred and Margaret Flowers, deeded Charles land in Wayne County where Charles and his wife, Rachel built a nice house architecturally reminiscent of the big house at Flowery Dale. It is in a state of ruin now, but it supports the strong family tradition that ‘Uncle Charles’ and ‘Aunt Rachel’ Flowers were people of quality and education, and they had a family of children all of whom were productive citizens of the region and always close to the Flowers family. In 1899 Robert Flowers deeded his own eldest son 50 acres adjoining that which he had deeded to Charles Flowers, and it was on this tract that my grandfather, John Baxton Flowers built his home in 1900 and where all his children were born, and played as children with those of ‘Uncle Charles’ and ‘Aunt Rachel.’

The other figure in the drawing of ‘Aunt Hannah’ and Charles, is her baby, Hephzibah, born in 1856, and who became my grandfather’s beloved ‘Aunt Hepsie’ who was his nursemaid as a boy. He loved and cared for her as long as she lived. He had such warm and wonderful stories of her and her place in the family circle. When the big house on the plantation caught fire early in 1878 and burned to the ground, it was ‘Aunt Hepsie’ who picked up my grandfather, then only four years old, and carried him and his sister Margaret, onto the lawn where they witnessed the house burning and all the people trying to get things from the house before they were burned. It was a memory that he and his younger sister Margaret, never forgot, nor did they ever have anything but wonderful things to say of’ Aunt Hannah’ and her children. To my knowledge there was never any public acknowledgement of the mulatto Flowers children as blood kin, but privately, there were close and warm relations. It has never been known who the father of Hephzibah was, but she too was a mulatto, as the census records will attest. She never married.

Tradition states that the sketch of’ Aunt Hannah’ and her children was done in a parlor of the big house on Flowery Dale, and the drawing shows a room that would date stylistically to about 1856. Note the dignity that is evident in ‘Aunt Hannah’s’ pose, and that of her son, Charles who by this time was waiting at table in the big house, and answering the door and doing odd jobs around the house. Tradition in the family says that ‘Aunt Hannah’ and her children and a few other slaves working in and around the house thought themselves ‘superior’ to the other slaves on the farms. Hannah’s influence was great with Alfred and Margaret Flowers. These mulattos took the family name Flowers when they were freed, and they remained with the family afterward for a long time.

Signed: John Baxton Flowers, III