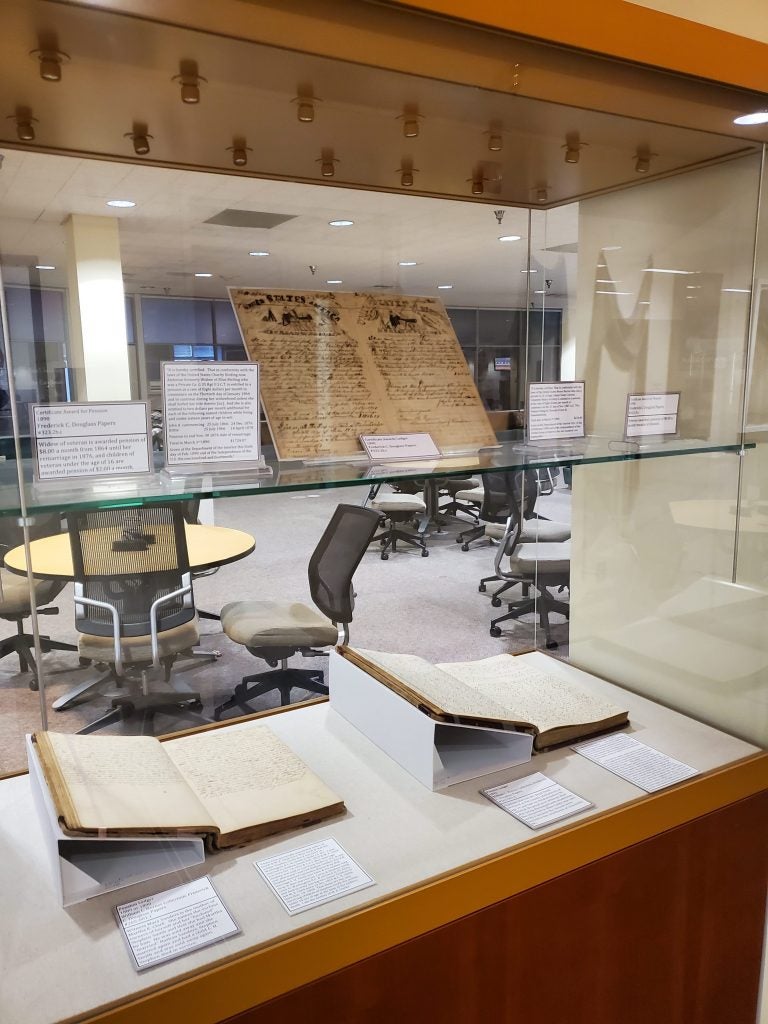

New Exhibit: “A look at New Bern’s Frederick C. Douglass, Pension Claims Agent, and African American Civil War Pension Ledgers”

A new exhibit entitled, “A Look at New Bern’s Frederick C. Douglass, Pension Claims Agent, and African American Civil War Pension Ledgers” and curated by Dale Sauter and Martha Elmore is currently on the 1st floor of the Joyner Library and will be available until May. The exhibit looks at the work of Frederick C. Douglass, a pension claim agent for the U.S. Pension Bureau, that handled claims for African Americans who served in the United States Colored Troops during the American Civil War.

When New Bern fell to Union forces in March 1862, many newly freed slaves in Craven County and the surrounding areas migrated there. In 1863, it became a recruiting headquarters for the United States Colored Troops. During the American Civil War, African American men enlisted in the Union Army and Navy as part of specially designated U.S.C.T regiments. They served in several different capacities including as cooks, and stewards, as well as being assigned to combat units.

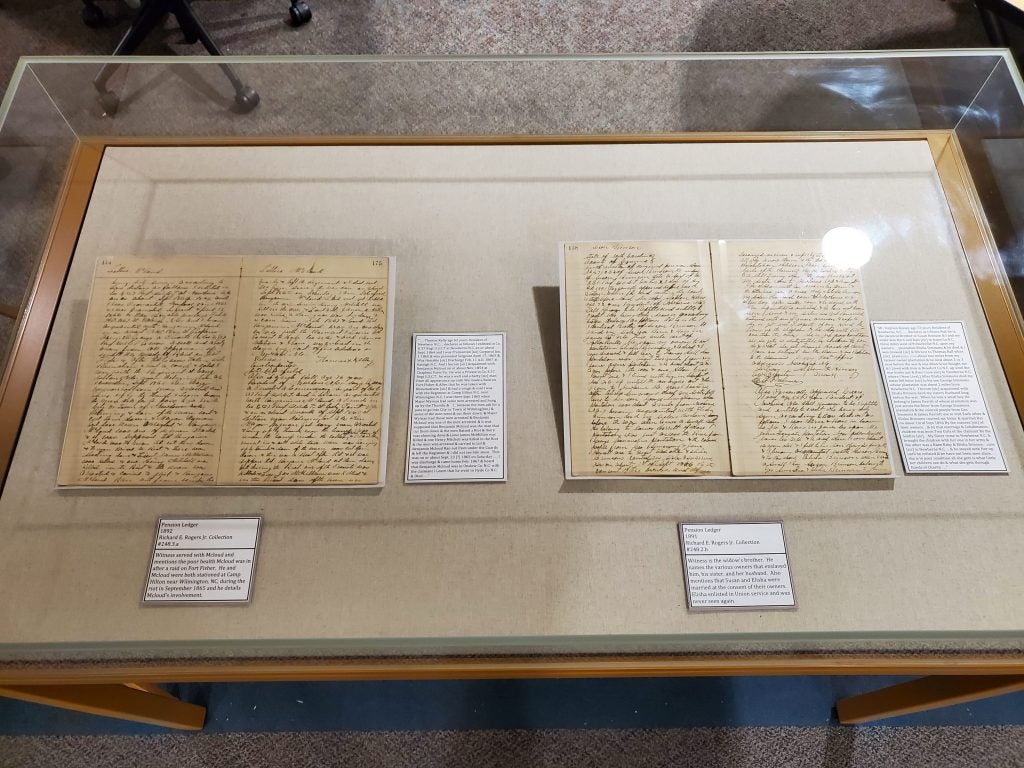

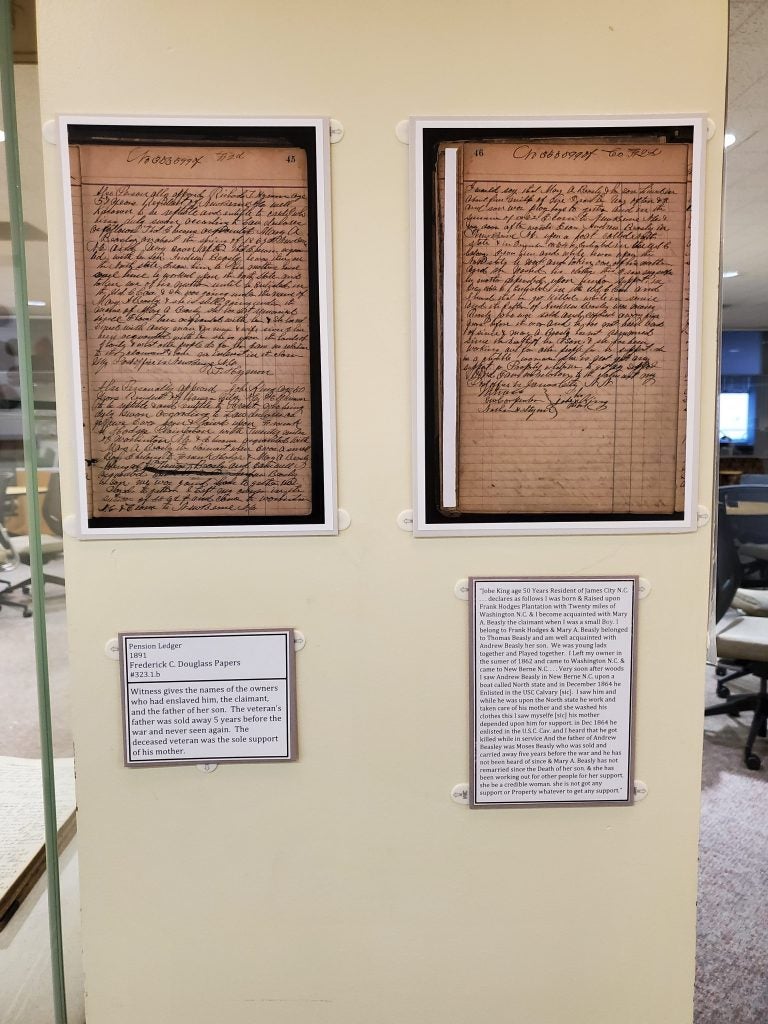

All veterans had to prove that they endured a disability during their Union service in order to get a pension. Douglass’1890s ledgers document cases where African Americans applied for pensions, although most of the claims represented here came from soldiers’ widows and minor children. Diarrhea, hemorrhoids, rheumatism, heart ailments, and gunshot wounds were common causes of disability. Some of the regimental groups represented in these pension ledgers are the 14th Regiment U.S.C.H.A., the 2nd Regiment U.S.C.C., 37th Regiment U.S.C.T. and the 35th Regiment U.S.C.T.

In each case, specific information was sought from witnesses familiar with the soldier’s life. Most witnesses were neighbors, friends, relatives, doctors, and other soldiers or sailors. Information given included the nature of relationships between the applicants and the witnesses, the ability of the applicants to support themselves, and in many cases, the continuing deterioration of the individual’s health. These claims contain a wealth of genealogical information concerning slave marriages and births, the names of former owners and plantations African Americans had lived on while enslaved, and marriage and medical certificates, in addition to information related to the Civil War.

These ledgers came to the East Carolina Manuscript Collection from three different donors and are found in the following collections: Frederick C. Douglass Papers #323 Richard E. Rogers Jr. Collection #248 and William L. Horner Collection: Frederick C. Douglass Papers #265-001.

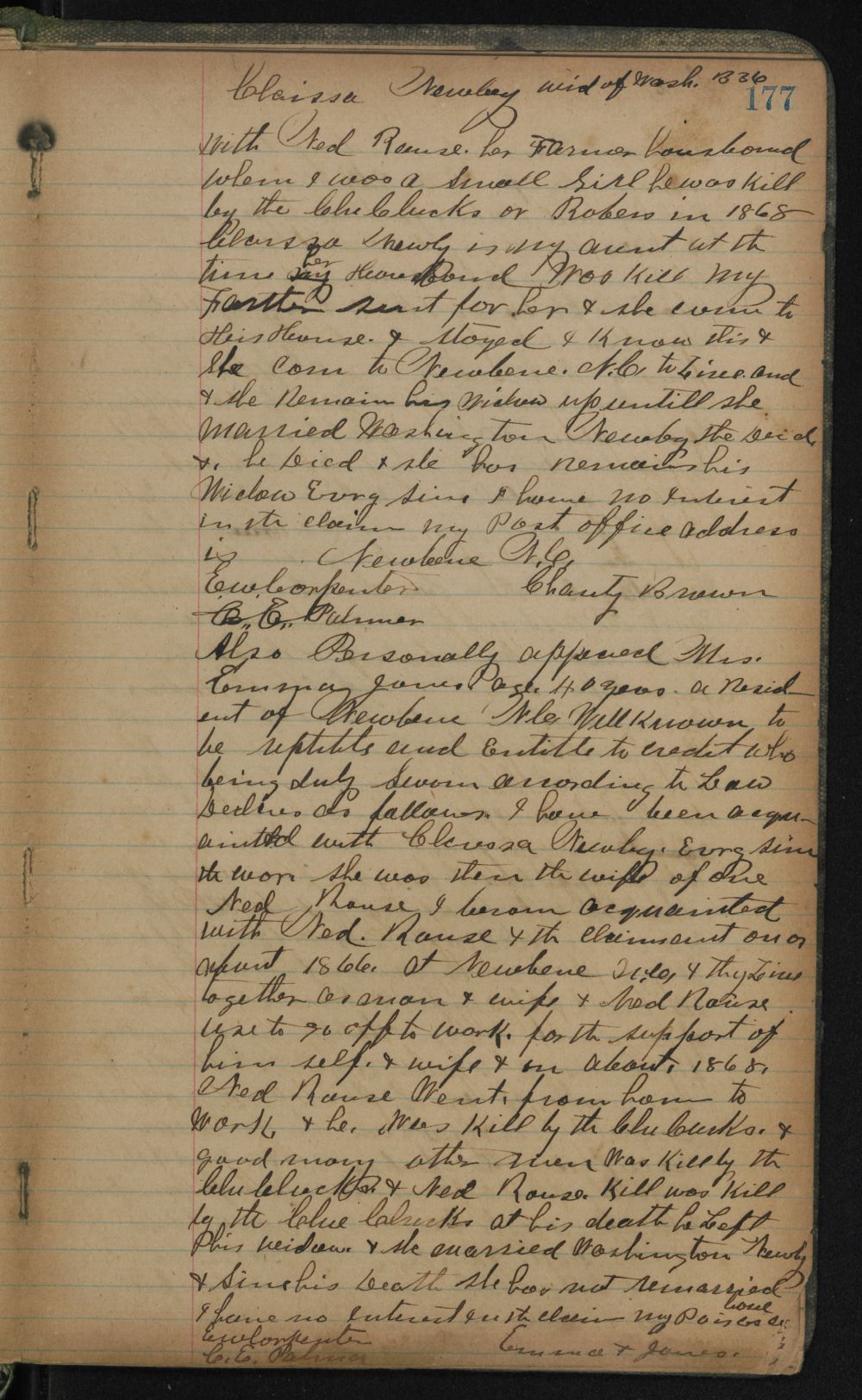

An example not included in the physical exhibit, but pictured here, is a claim from Clarissa Newby seeking a pension based on her deceased second husband’s military service. This claim is part of an 1891 ledger contained in #323.1.c, Frederick C. Douglass Papers. The death of Clarissa Newby’s first husband, Ned Rouse, is discussed in the affidavit of witness Mrs. Emma Jones. Mrs. Jones states that: “I became acquainted with Ned Rouse & the claimant on or about 1866 at Newbene [sic] N.C. & They Live together as man & wife and Ned Rouse use to go off to work for the support of him self & wife & on about 1868 Ned Rouse Went from home to work & he was Kill by th[sic] Clu [sic] Cucks [sic] & good many other men was Kill by th[sic] Clu [sic] Clucks [sic].”

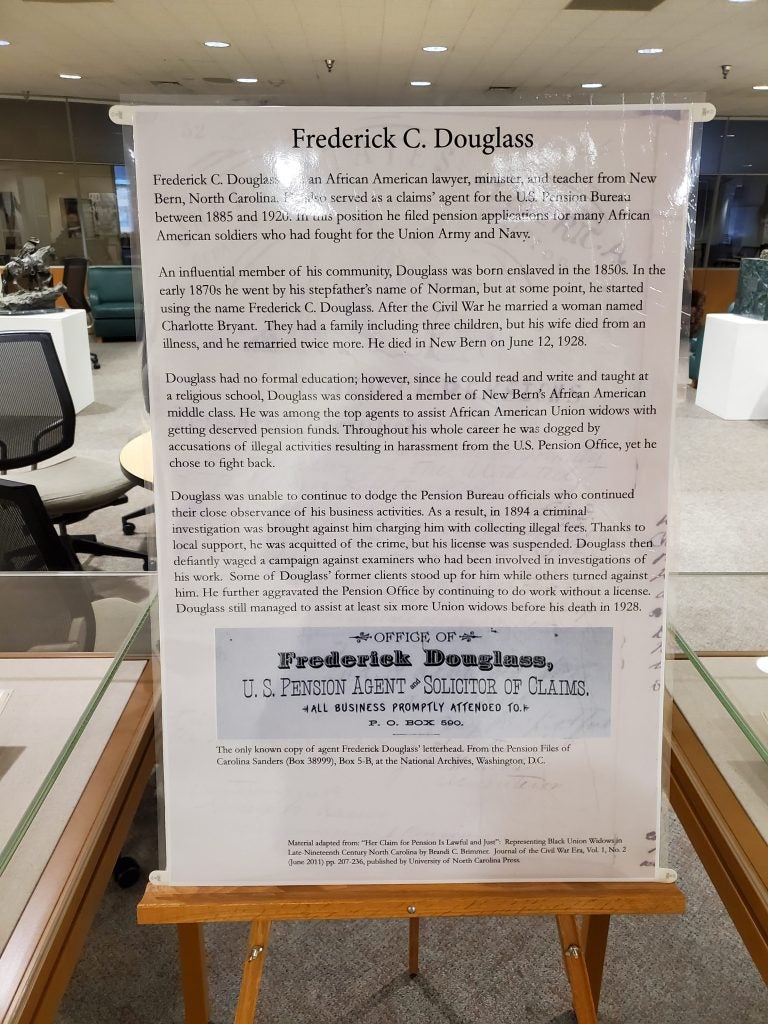

Frederick C. Douglass (no kin to the famous abolitionist Frederick Douglass) was an African American lawyer, minister, and teacher from New Bern, North Carolina. He also served as a claims’ agent for the U.S. Pension Bureau between 1885 and 1920. An influential member of his community, Douglass was born enslaved in the 1850s. In the early 1870s, he went by his stepfather’s name of Norman, but at some point, he started using the name Frederick C. Douglass. Douglass was considered a member of New Bern’s African American middle class. He was among the top agents to assist African American Union widows with getting deserved pension funds.

Throughout his career he was dogged by accusations of illegal activities resulting in harassment from the U.S. Pension Office. In 1894, a criminal investigation was brought against him charging him with collecting illegal fees. Thanks to local support, he was acquitted of the crime, but his license was suspended. He further aggravated the Pension Office by continuing to do work without a license. Douglass still managed to assist at least six more Union soldiers’ widows before his death in 1928.

Material concerning Frederick C. Douglass adapted from: “Her Claim for Pension Is Lawful and Just”: Representing Black Union Widows in Late-Nineteenth Century North Carolina” by Brandi C. Brimmer. Journal of the Civil War Era, Vol. 1, No. 2 (June 2011) pp. 207-236, published by University of North Carolina Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26070114.